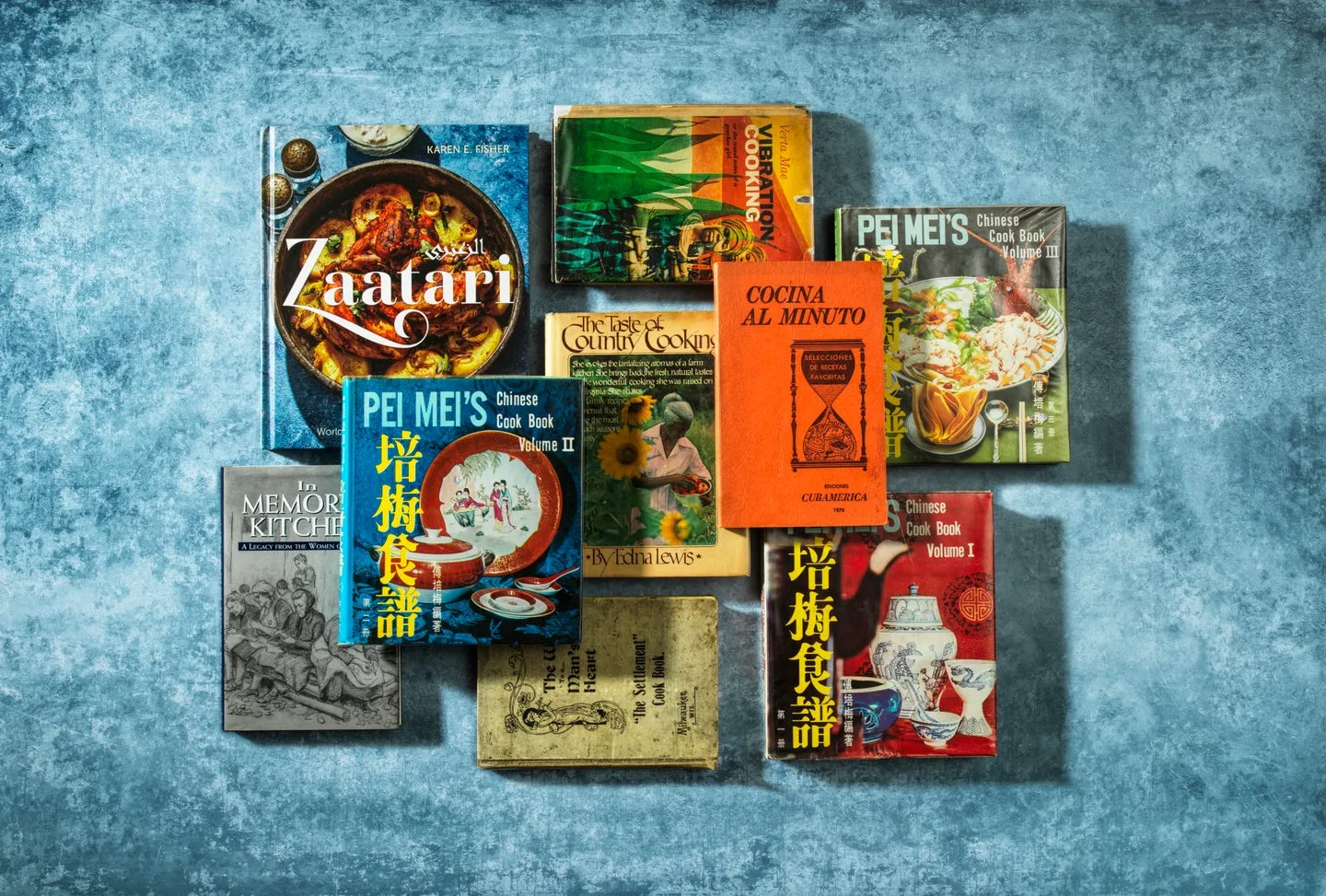

In Zaatari, the world’s largest Syrian refugee camp, the scents of roasting coffee, freshly baked khubz bread, and frying onions fill the air. As an ethnographer conducting research in the community of 83,000 on the Jordanian border, Karen E. Fisher has come to recognize these smells as an invitation to the community’s many gathering spaces. Even a simple breakfast here can be high art, an ornate assembly of home-cured olives, ful mudammas (cumin-scented fava bean stew), and tesqieh (chickpeas in garlicky yogurt). Since 2016, Fisher has worked with the women of the camp to gather their recipes into a community cookbook that bears its name: Zaatari. Far from being defined exclusively by hardship, the book channels the resilience of a people and of a neighborhood with its own rich food culture.

Making dishes from Zaatari—or any of the many 20th-century cookbooks that bring politics to the table—highlights what even some cookbook aficionados struggle to accept: The kitchen is not always an escape from the realities of the world. For many, cooking is an inherently political act, and any dish can represent an attempt at self-determination.

One of the first explicitly political recipe books published in the United States was The Settlement Cookbook. The 1901 manual compiled homemaking tips from a Milwaukee, Wisconsin community center founded by Progressive-era reformer Lizzie Black Kander to support Jewish immigrants. In addition to instructing readers on American dietary standards, Kander shared recipes drawn from what she cooked in her own Jewish household.